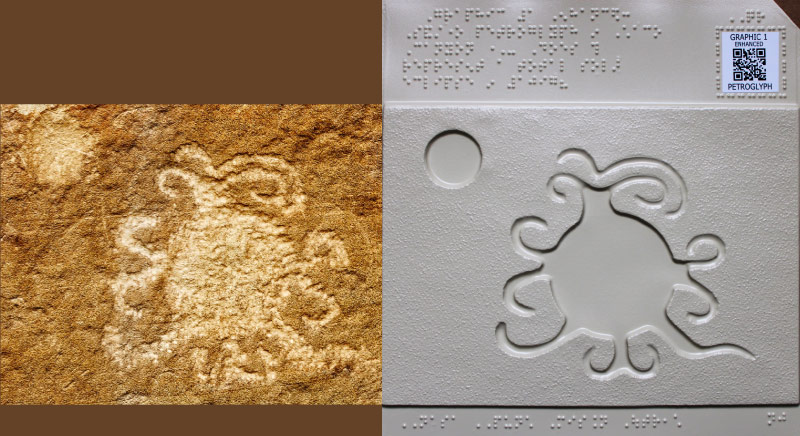

Graphic 1 enhanced: Sandstone petroglyph in Chaco Canyon - Does this represent a total solar eclipse in 1097?

Welcome to Tactile Graphic number 1 - the Chaco Petroglyph! This is the starting point for the “Petroglyph Inquiry” - an authentic inquiry activity that guides both blind and sighted learners through a set of seven tactile images in the particular order offered in the Navigation Index at the bottom of the page. Read more about this opportunity at the Home Page - Petroglyph Inquiry.

Whether you are engaging fully with the Petroglyph Inquiry (recommended) or just browsing the PUNCH Outreach set of seven images in a random order, we strongly encourage you to begin by reading the 2-page section, entitled Essential Background. This will support an enjoyable learning experience by increasing your basic familiarity with:

- Chaco Canyon and the Ancestral Puebloan people

- Solar Eclipses and the Sun’s Corona

- The NASA PUNCH Mission, Solar Storms, and the Sun’s 11-Year Sunspot Cycle

Guided Description of the Tactile Graphic number 1

The tactile image between the Braille areas at the top and bottom of Graphic 1 represents an enhancement of the key features of a petroglyph (rock carving) engraved into a sandstone rock wall in a place called Chaco Canyon more than nine centuries ago. Ancestral Puebloan people residing in the Canyon created this carefully and artistically rendered petroglyph. Their descendants still live in the Chaco region. These are the people of Acoma, Hopi, Zuni, and many other modern Pueblos in the Southwestern US. Our Puebloan colleagues tell us that whatever the meaning of this petroglyph, it was important to their ancestors and remains important today.

We invite you to touch this tactile representation with cross-cultural awareness, appreciation, and respect.

The “sunken-in” nature of the central disk and other features is real but exaggerated compared to the actual petroglyph. A rough, sandpaper-like texture represents the sandstone rock wall in which the petroglyph was engraved. The creator of the petroglyph used stone or bone tools to alter this background texture and thereby make the figure become visually distinct from its background. The tactile image in Graphic 1 enhanced uses a smooth texture to represent what a sighted learner perceives on the rock. A previous version of this graphic used a dimpled texture for this purpose. We wanted the dimples to represent the appearance of the petroglyph having been pecked into the rock face. However, in the thermoform medium, it was too difficult to make this texture consistent and tactilely vivid enough, especially in the small curlicues.

Please explore the image with your hands to find all the key features listed below:

- A central circular disk

- Curlicue features emanating in all directions from the central disk (How many? Are they all the same?)

- A distinctive, double curlicue feature at the top of the central disk – one curlicue feature beneath another

- A distinctive, tail-like feature extending from the central disk. (Can you find where this occurs?)

- A smaller circular disk to the upper left of the main part of the petroglyph. (What could this represent?)

The width of the real petroglyph’s central disk is about four inches (10 cm) across. If you include the curlicue features extending to either side of the disk the width doubles to about eight inches (20 cm) across. This is about the distance between thumb-to-pinky on an adult human hand with fingers spread wide. Thus, the tactile representation you are touching is not quite full scale. It is about two-thirds of the actual size.

Up to now we’ve been describing the petroglyph in ways everyone can agree upon (its size, location, and key features). But what about interpreting the petroglyph? An interpretation of the petroglyph is different than a description. Interpretation depends a lot on your individual prior experience and knowledge. Interpretation asks you to consider what you think the petroglyph represents, and this can be very different for different people.

In the early 1990's, Dr. Kim Malville was the first Western solar astronomer to suggest that the Chaco petroglyph may represent the total solar eclipse of July 11, 1097 as it was viewed during the few minutes of totality. Totality is when the Moon totally blocks the bright light of the Sun’s disk and allows the Sun’s outer atmosphere called the solar corona to become visible to human eyes.

Dr. Malville further suggested that the “curlicued” petroglyph may reflect Chacoan observers’ impression of a solar storm called a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) ongoing in the Sun’s corona during totality. In news stories and this 2-minute Scientific American podcast leading up to the 2017 Great American Eclipse, Dr. Malville admitted his bias for a Sun-related interpretation of the petroglyph. As a solar astronomer, he had seen many contemporary images of solar eclipses, the solar corona, and solar storms like CMEs that can curl or otherwise distort the coronal rays.

We can never be completely certain of what this ancient rock art represents, but we can come up with multiple ideas or hypotheses about how to interpret the figure, and then consider evidence that strengthens or weakens a particular idea. The dictionary defines “hypothesis” as: “a proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.”

Because we are interested in ancient and modern Sun-watching, we are most intrigued to use Dr. Malville’s “1097 eclipse with a storm” hypothesis for the Petroglyph Inquiry. However, we must remember that there are other hypotheses that could have served as our starting point.

REFLECTION

In this spirit of considering multiple hypotheses, try to think of at least three other possible interpretations of the curlicue petroglyph based on your own prior knowledge and experience of the shapes and forms you have experienced.

After you have your ideas recorded, we invite you to continue participating in the Petroglyph Inquiry by reading the Additional Commentary below. The Commentary will share with you the initial impressions of Chaco visitors when first seeing the curlicue petroglyph so you can compare with the alternative interpretations you thought of.

Please note that the Additional Commentary for Graphic 1 is longer (3 pages) than those for any of the other Graphics. We hope you find it fun, enriching, and supportive of developing your own perspective on the interpretation of the curlicue petroglyph.

Graphic 1: ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY for those doing the PETROGLYPH INQUIRY

Like Dr. Malville, Dr. Cherilynn [SHARE-ril-lin] Morrow is a solar astronomer by academic training. She is also an educator at heart and singer-songwriter by soul. She leads the amazing NASA PUNCH Outreach team – whose members and collaborators have created the set of images and thermoform tactile-art graphics you are exploring. Dr. Morrow is the lead author of this Petroglyph Inquiry because she has spent many years as a Chaco volunteer, observing and guiding visitor education programs at the cultural site where the curlicue petroglyph is located. She reports that Chaco visitors offer a wide variety of initial ideas about what the petroglyph “looks like” to them, meaning how they interpret the petroglyph based on their prior knowledge and experience.

Dr. Morrow tells us that a frequent first impression for visitors is "Octopus." Other relatively common responses for sighted people are "tick or spider” or "some kind of flower, plant, or vine.” Still others have interpreted the petroglyph as a “fire” around which some sort of festive activities are occurring since there are several other petroglyphs located on the same rock face, including flute players, at least one four-legged animal, plus other human-like figures, some of whom appear to be dancing.

REFLECTION

How do the above interpretations from Chaco visitors compare to the alternative interpretations that you thought of earlier?

Of course, “Octopus” is a relatively easy interpretation to rule out based on its lack of connection to Chaco’s environment or culture. But "spider", "flower", and "fire" all remain viable interpretations given that they are natural parts of Chaco’s high-desert climate and culture.

Plants and flowers are a source of food and are thus deeply important to the survival of a farming culture. If the petroglyph represents a culturally important flower, instead of an eclipsed Sun, how could the features of the petroglyph be explained?

Because PUNCH is a NASA mission to explore the Sun, we are especially interested in using ancient, historical, and contemporary observations of the both the petroglyph site and the Sun’s corona to inquire more deeply into the strengths and weaknesses of the “eclipse hypothesis.”

Please pause to begin your own list of strengths, weaknesses, ideas, and questions regarding the “1097 eclipse” hypothesis for interpreting the Chaco petroglyph. What do YOU think at this point? What else would you want to know before deciding whether the “1097 eclipse” interpretation is the most reasonable one for the petroglyph compared to simpler interpretations like “Tick or Spider”, “Flower or Plant” and “Fire”? There is no right or wrong answer, only evidence that strengthens or creates uncertainty about a particular interpretation.

In pursuit of evidence for a particular hypothesis a good scientist raises challenging questions that test a hypothesis to see how well it holds up under scrutiny. We invite you to consider the five questions and answers provided below and to use them to continue developing your list of strengths and weaknesses of the “1097 solar eclipse with a solar storm” hypothesis.

How likely is a solar storm to occur during the totality phase of a solar eclipse?

There is scientific evidence to suggest that 1097 was a time of maximum sunspot activity on the Sun (Vaquero & Malville 2014). This makes solar storms more likely to occur. During solar maximum, there are up to three Coronal Mass Ejections per day on average compared to solar minimum when on average there is only about one CME every five days. On the other hand, for the 1097 solar eclipse, the totality phase of the eclipse, during which the solar corona could be observed, lasted only about three minutes over Chaco Canyon. Still there have been occasions when modern observations of the corona during an eclipse have detected the signature shapes and distortions of a solar storm.

How certain are we that the Chaco residents actually observed the 1097 eclipse?

We cannot be completely certain, but we can consider how likely it is. The 1097 total solar eclipse of the Sun occurred over the Chaco region in the mid-afternoon of July 11th. Archaeologists tell us that 1097 was a time of peak human activity in the Canyon, still within the prime time of constructing Chaco buildings. Early July is soon after the summer solstice, a culturally important time of year for tending crops and praying for rain. It is a time of year when the Ancestral Puebloan people would have been especially attentive to the behavior of the Sun and Moon and using them to track time in support of agriculture and ceremony. If the clouds of a monsoon rainstorm did not inhibit the view, the Chaco residents could not have missed the spectacle of the eclipse. And even if the event were obscured by clouds, they would have noted the darkness and dramatic cooling in the middle of a midsummer day. It is possible that the ancient observers caught only a glimpse of the eclipse through partly cloudy skies. Could the curlicues of the petroglyph represent billowing clouds instead of the solar corona?

Is there evidence that Sun-watching was important to the Chaco residents? Did they know how to predict eclipses?

There is abundant evidence in the Canyon for Sun-watching mastery. Examples include the astronomically alignments of Chaco buildings, the use of light and shadow on spiral petroglyphs to mark culturally important times of year, and the use of the changing position of sunrise and sunset on a horizon to track time and seasons in support of agriculture and ceremony. This same sort of evidence for ancient Sun-watching extends throughout a much vaster region of the Four Corners region where New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah now share borders. Today some of these places are familiar National and State Parks like Chimney Rock, Bears Ears, Mesa Verde, and Hovenweep. Almost all contemporary Pueblos have sustained their ancient Sun-watching traditions, while also participating with NASA and other modern means of observation.

There is concrete evidence that the ancient Mayan and Aztec cultures to the south of Chaco (in modern-day Mexico) knew how to predict eclipses. Mayan culture rose and fell in the centuries before the dawning of Chaco culture in 800 CE and there is definite material evidence of cross-cultural contact. The rise and fall of the Aztec empire (1300s to the 1500s) followed the flourishing of Chaco culture (800 and 1250 CE). Unlike the Maya and Aztec cultures, Chaco culture did not leave a systematically readable description of their astronomical understandings. From an archaeological point of view, we can only interpret what Ancestral Puebloans understood about astronomy from the artifacts, buildings, and rock carvings left behind. We can also speak with their Puebloan descendants, some of whom have been told that their ancestors knew how to predict eclipses. Of course, eclipses are not rhythmic occurrences for a particular place on Earth in the same ways as solar and lunar cycles are. Using today’s astronomy software that any of us can have access to, we can determine that total solar eclipses occurred over the Chaco region in 804, 1097, and 1257.

Is there evidence for the petroglyph being situated in an ancient Sun-watching context?

Yes. Chaco itself is a Sun-watching context, but there is also evidence for specific types of ancient Sun-watching that are nearby the petroglyph. Mr. G B (Gee Bee) Cornucopia is an interpretive ranger who retired in 2022 after 30-plus years of service in Chaco Canyon. In the early 1990s he was a research assistant to Dr. Malville, making the first photographs of dramatic sunrises near the time of summer solstice that occur when viewed from a spiral petroglyph that is just around the corner from the “curlicued” petroglyph on the eastern facet.

Dr. Morrow and her team are now collaborating with Mr. Cornucopia, Dr. Malville and others to re-evaluate the “eclipse hypothesis” for the petroglyph. This has engaged the PUNCH Outreach team in making comprehensive, culturally respectful photographic documentation of the site where the Chaco petroglyph is located. Using leading-edge camera equipment and post-processing techniques, we have documented significant sunrises and sunsets from the east and west rock facets on either side of the southern facet that includes the curlicue petroglyph. In the process we have documented new information about how Chaco Sun-watchers may have used the eastern horizon to track time and seasons in support of agriculture and ceremony.

Of course, the petroglyph’s location in a rich ancient Sun-watching context doesn’t prove the “eclipse hypothesis” but it does help to strengthen the case for why a Sun-related petroglyph might have been placed nearby.

On the other hand, a remarkable anthropologist named Florence Hawley Ellis published a critique in the 1970s arguing that Ancestral Puebloan people were not likely to have recorded an impression of a one-off historical or celestial event in their rock paintings and carvings. She suggested on the basis of documented conversations with Puebloan descendants that they were far more likely to create enduring impressions of predictable phenomena that were observed to repeat, such as the cycles of the Sun, Moon, and stars, and thereby be of ongoing benefit to agriculture.

What did Chaco residents make of the 1097 total solar eclipse? Did they think it was possible that it would return and thereby recorded it and kept watching? Could they have predicted the eclipse and, if so, then perhaps they were celebrating their success with the “party-like” rock art panel that includes dancers and flute players around the curlicue petroglyph.

Are there other examples of the curlicue design in Chaco Culture? Do we have any other clues for interpreting the petroglyph’s design?*

Yes, Dr. Morrow has initiated an ongoing project to search available research collections for examples of pottery with potentially Sun-themed designs. This was motivated by her discovery of two pieces of black-on-white pottery associated with Chaco Culture that display curlicue designs with a striking similarity to the petroglyph.

One of the pieces juxtaposes a curlicue design with a more familiar Sun design - two concentric circles, each with radial lines emanating in all directions. The combination of designs on this pot is supportive but not conclusive evidence of a solar interpretation for (or at least association with) the curlicue design motif.

Dating pottery is hard, and experts have only been able to make estimates in 50 to 100-year chunks of time for these two pieces of pottery. These time periods overlap or bracket the 1097 eclipse, but it requires more research to say whether the curlicue design on these ancient pots was inspired by the 1097 total solar eclipse or whether the design was already an artistic motif in Chaco culture prior to the eclipse for representing the Sun, or perhaps even for representing something else that is important to the culture.

REFLECTION

In light of the answers to these questions, please pause to add to your own list of strengths, weaknesses, ideas, and questions regarding the “1097 eclipse” hypothesis for interpreting the Chaco petroglyph.

When you are ready, click the NEXT button below to go to Graphic 2, which is an 1860 hand drawing of a total solar eclipse.