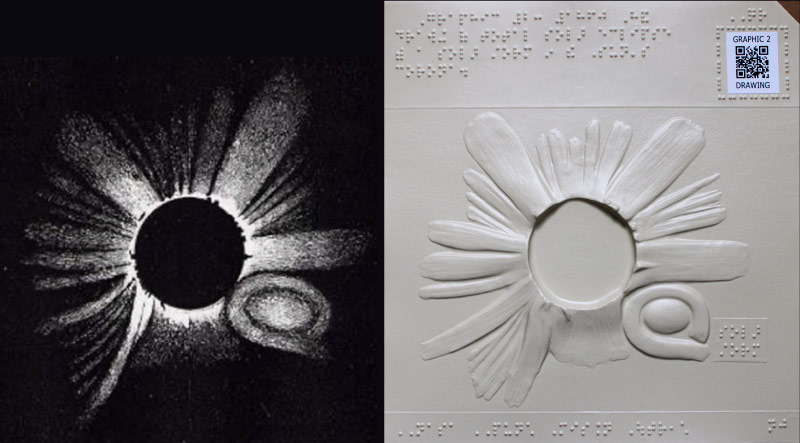

Graphic 2: 1860 Hand drawing of total solar eclipse with a solar storm in the Sun’s corona

Welcome to Tactile Graphic number 2 – the 1860 Hand Drawing! This is the second of seven images supporting the Petroglyph Inquiry.

Whether you are engaging fully with the Petroglyph Inquiry (recommended) or just browsing the PUNCH Outreach set of seven images in a random order, we strongly encourage you to begin by reading the 2-page section entitled Essential Background if you have not already done so.

Guided Description of the Tactile Graphic number 2

The tactile image between the Braille areas at the top and bottom of Graphic 2 represents a hand-drawing of the solar corona made by European astronomer Guglielmo Ernesto Tempel. The drawing depicts the totality phase of a solar eclipse that occurred on July 18, 1860. Mr. Tempel’s drawing is based on observations he made with his now famous 4-inch refractor telescope from a town on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea called Torreblanca, Spain.

In 1860, cameras were only just beginning to be used for recording eclipses. It was during this very eclipse that observers first recorded photographs from different locations that were then considered together to determine for sure that the glow of the corona during totality was part of the Sun rather than being part of the Moon or a phenomenon in Earth’s atmosphere.

Nonetheless, in 1860 there were still human eye observations, like Mr. Tempel’s, recorded by observers all along the path of totality from Canada to North Africa. The human eye and brain were (and still are) able to perceive coronal detail farther out from the Sun than the single-exposure photos of that time. These days, special filters and the combining of multiple exposures can create ground-based images that detect more detail in the solar corona than human eyes.

Meanwhile, Mr. Tempel was especially well known for being a sharp-eyed observer of the heavens. Using his telescope, he was the first to discover many faint asteroids and comets. Thus, it is not surprising that he perceived something in the solar corona during totality that other observers did not.

Please pause to explore the tactile image, be sure to find the features listed below:

- A central circular disk representing the Sun eclipsed by the Moon

- Long rays and streamers of the solar corona extending out in all directions from the central disk

- An oval-like shape in the solar corona. Where is this feature located?

Tempel drew an oval-shaped feature in the corona that no other observer recorded. The peculiar feature had not been documented by Western science and was not understood at the time.

Just as for rock art, features in the solar corona can be both described and interpreted. Tempel’s hand-drawing provided a courageous description of the never-before-seen oval feature, but the correct scientific interpretation of what he observed was unavailable for more than 100 years afterward!

NASA images made in the early 1970’s used a special instrument that artificially blocks the light from the Sun’s disk to reveal the outer solar corona. This is called a coronagraph. A space-based coronagraph first revealed that tons of solar material could leave the Sun, explosively ejected away from the corona, never to return. In 1974, a historically attentive astronomer named John Eddy published a paper that re-visited Tempel’s 1860 drawing and compared it to early coronagraph images of then-called “bubble transients.”

Today, the interpretation of the oval-shaped “bubble” is known with virtual certainty. It is the well-recognized shape of a solar storm in progress in the corona that we now call a Coronal Mass Ejection, or C-M-E (see-ehm-ee) for short. A C-M-E is a solar storm that can curve or otherwise distort the rays of the solar corona as it erupts.

REFLECTION & DISCUSSION

Could one or more CMEs be related to our interpretation of the curlicue features of the Chaco petroglyph (Graphic 1)? How does Graphic 2 influence your thinking?

Graphic 2: ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY for those doing the PETROGLYPH INQUIRY

The four additional comments below are intended to enrich and support your participation in the “Petroglyph Inquiry.” As you read them, please continue with your list of strengths, weaknesses, ideas, and questions regarding the “eclipse hypothesis” for interpreting the Chaco petroglyph (Graphic 1).

- In 1859, about a year before the eclipse that Tempel and others observed, the Sun released the most powerful solar storm ever recorded. This was the so-called Carrington Event, named for one of the astronomers who happened to be observing through a large telescope when an intense flash of light occurred on the Sun. The years 1859 and 1860 were during a period of high solar storminess on the Sun that we call a Solar Maximum. Periods of solar maximum generally last for 2-3 years and occur about every 11 years.

- The 1860 hand drawing provides solid evidence that humans have observed the signs of a solar storm during the few minutes of eclipse totality. Observing the corona during a period of solar maximum makes it more likely, but not certain, that a storm could occur that is strong enough to be perceived by an Earth-based human eye during the brief time of totality.

- But could the observers of the 1097 eclipse in Chaco have detected something like this? Tempel was using his telescope to make his 1860 coronal observations. His perception of the oval-like feature may or may not have been perceivable to the human eye without the magnification of his telescope.

- Yet Chaco observers would also have been keen-eyed and perhaps observing with clearer, desert air? And perhaps they witnessed an especially strong episode of storminess that made changes in coronal structure more obvious to the unaided eye?

REFLECTION

What do you think? Please add to your list of strengths, weaknesses, ideas, and questions regarding the “1097 eclipse” hypothesis for interpreting the Chaco petroglyph.

When you are ready, click the NEXT button below to go to Graphic 3, which is a 1918 painting of a total solar eclipse.